On 27 February 2024, the Afghanistan Journalists Center (AFJC), and prominent local media outlets including Independent Persian and Amu TV, reported that during a meeting with media representatives in Kabul, the officials of the Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Evil (MPVPE) requested that female moderators appear on TV in full veiling with the niqab, covering their faces except for their eyes, and adhering to a modest dress code.

According to the AFJC and sources quoted by Amu TV, Mohammad Khaled Hanafi, the Taliban’s Acting Minister of the MPVPE, warned about the possibility of a complete ban on women’s work in media if they failed to adhere to the guidelines regarding their appearance. According to the AFJC, Abdul Ghaffar Farooq, a MPVPE spokesman, suggested that the media organisations should avoid interviewing Afghan women who do not fully cover their faces.

Although the measure was announced in Kabul, Afghan Witness (AW) has understood this to be implemented nationwide. It follows a previous decree issued in May 2022, when the Taliban ordered female anchors and other women appearing on TV to cover their faces on air.

Local media prohibited from accepting calls from women and girls in Khost

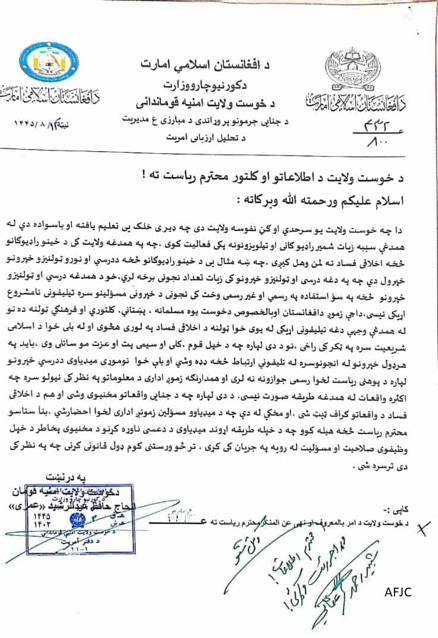

On 25 February 2024, Radio Azadi and the AFJC reported that Taliban authorities in Khost banned local media, including radio stations and television channels, from accepting phone calls from girls and women, effectively prohibiting the broadcast of women and girls’ voices. This order was issued in a letter, addressed to the Khost Department of Information and Culture, and shared by AFJC; the letter was issued by the Ministry of Interior and the Khost Police, dated 24 February 2024, and signed by Khost Police Chief Abdul Rashid Omari (below).

Figure: Official letter ordering the ban on girls’ calls to the local radio stations in Khost.

In addition to banning girls’ phone calls to the local radio and media, the letter accused “some” private radio stations in Khost of “promoting moral corruption” by broadcasting school lessons or social programs in which girls allegedly participated. It claimed that the girls “abuse” these programs to make “illegal” phone calls with the organisers, which allegedly leads to “moral corruption” and goes “against Islamic standards.” The letter also stated that local radio and television channels do not have permission from the Department of Education to broadcast educational programmes, and warned that if local media continue to provide these programs, their executives would be summoned and prosecuted.

Female radio hosts reportedly banned in some provinces

Beyond the prohibition of local media accepting calls from women and girls in Khost, Zan Times reported on 29 February 2024 that women were no longer permitted to work as radio hosts in the province. The outlet similarly reported that women were banned from working as radio hosts in Kandahar and Ghor provinces. These alleged prohibitions follow similar restrictions implemented in Helmand province in August 2023, where the Taliban’s Information and Culture Ministry ordered local radio stations to cease broadcasting women’s voices – including in advertisements. At the time, Helmand was understood to be the only province where such an order was implemented.

According to Zan Times, the Taliban have implemented further media restrictions across Afghanistan. In Kandahar, journalists are now banned from publishing people’s complaints against the Taliban. Also in Kandahar, Zan Times claims that male journalists are now required to grow beards and abstain from wearing ties, and are forbidden from interviewing women. In Ghor, all female journalists have been banned from appearing in public in the province, in addition to the ban on working as radio hosts. In Takhar, Zan Times reported that journalists and local media were told to consider “national interests and religious values” while completing their day-to-day tasks. AW investigators have been unable to independently verify these reports.

Photography and filming of local Taliban officials prohibited in Kandahar

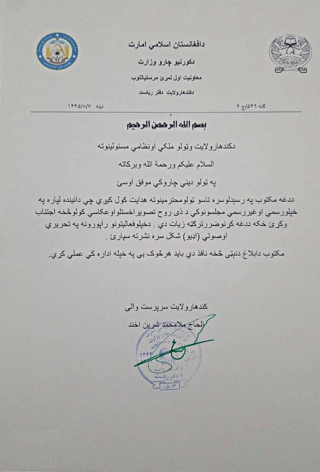

On 18 February 2024, Independent Persian shared a post claiming that Taliban authorities in Kandahar banned photography and filming at meetings of local officials, reminiscent of media restrictions under the Taliban in the 1990s. The AFJC corroborated this claim in a press release on 19 February 2024, sharing a copy of an official letter signed by the Taliban’s acting Governor of Kandahar, Molla Shirin Akhund, as seen below.

Figure: Official letter banning photography and filming in official and unofficial meetings of local Taliban officials in Kandahar.

The letter instructs local and military Taliban officials in Kandahar to prohibit photography and filming of their gatherings; instead, reports related to officials’ work will be published in written or audio form. According to the AFJC, the order has already led to difficulties in conducting interviews with local officials.

The implementation of the order has already been observed on local media channels, including Radio Television Afghanistan (RTA) Kandahar, which stopped sharing videos and pictures of Taliban officials’ meetings and events on X (formerly Twitter) after 18 February 2024, replacing them with videos of landscapes, cityscapes and buildings. An exception was the 3 March 2024 visit of a delegation of officials from the Taliban’s Ministry of Agriculture to Kandahar, related to the construction and distribution of greenhouses to farmers in the province. Based on the video shared on X, in which Taliban officials are clearly seen, it appears that the group, from outside Kandahar, may have been exempt from the order. Before and on 18 February 2024, the RTA Kandahar accompanied daily news posts with pictures and videos of Taliban officials. It is noteworthy that the order does not appear to apply to visits and meetings outside of Kandahar, in other provinces or abroad.

Similar changes were observed on the Government of Kandahar Media and Information Centre’s X account, which stopped sharing pictures and videos from Taliban officials’ meetings and began sharing written statements instead. Inamullah Samgani, the head of this provincial ministry, also appeared to implement the order.

Although this measure is currently confined to Kandahar province, it is representative of the Taliban’s interpretation of Sharia, specifically Hadith prohibitions on the production of imagery of living beings. It is therefore possible that such measures could extend beyond Kandahar in the future, effectively replicating the ban implemented by the Taliban in the 1990s. One significant difference in the present, however, is the widespread use of smartphones and social media, and the Taliban’s penchant for using videos and photos recorded on smartphones for their own propaganda materials.