CIR collaborated with DW to investigate the targeting of civilians and vehicles in the Ukrainian city of Beryslav.

Aerial footage of a drone attack on a vehicle. Source: Telegram

This article contains details that some readers may find distressing. CIR has redacted most links due to privacy concerns, graphic footage, or to avoid amplifying content.

In one video, a man clutches his arm, a pool of blood at his feet, as Ukrainian soldiers attempt to bandage his wounds. A photograph of another incident shows a mangled blue sports car, its windscreen completely caved in. Inside, a 34-year-old woman was reportedly killed and her 36-year-old husband seriously injured.

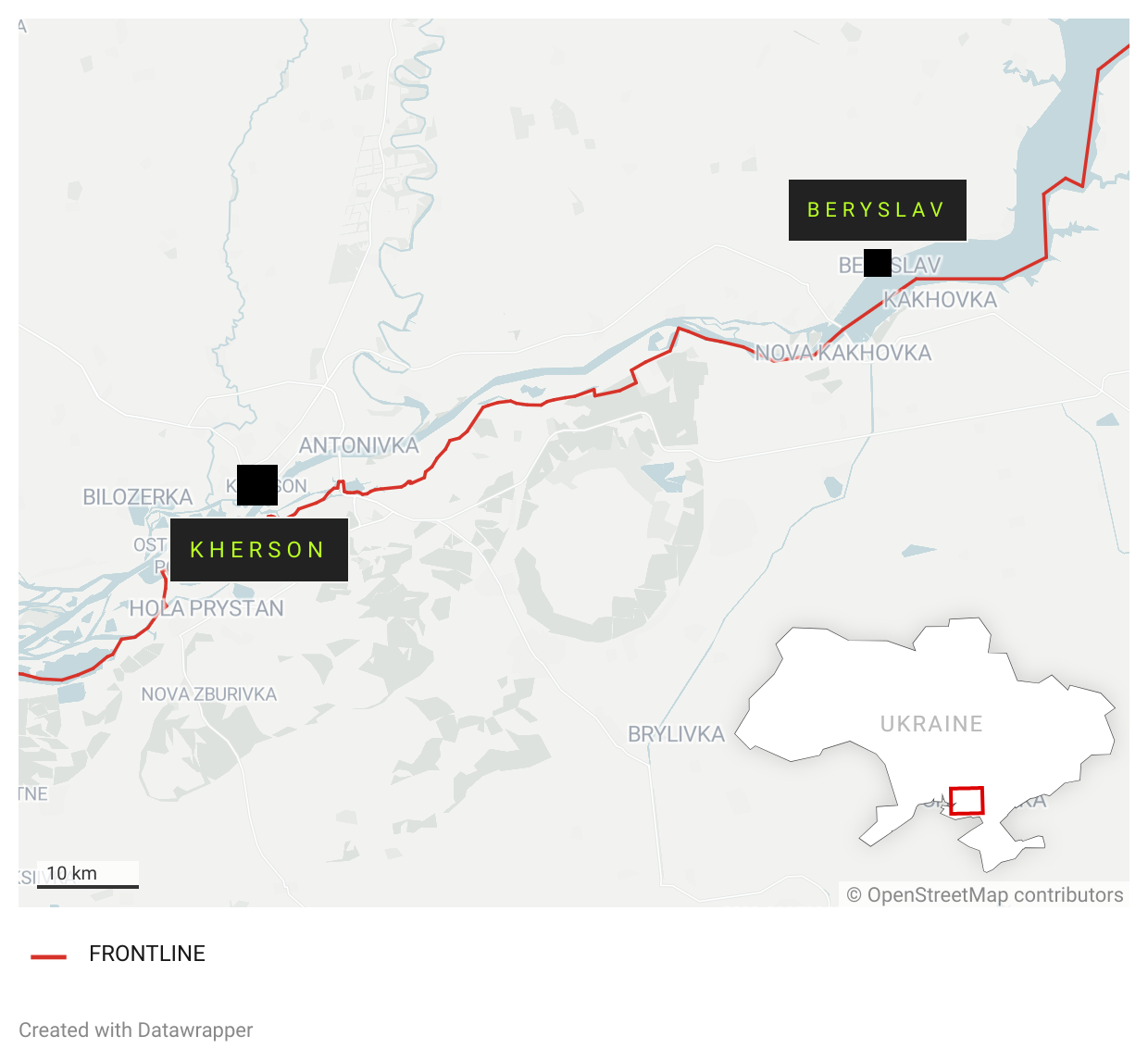

This is just a glimpse of the reality uncovered by open source footage of Russian drone attacks in Beryslav – a small city on the west bank of the Dnipro River, a key strategic front in Russia’s war on Ukraine.

An investigation carried out by DW Investigations, supported by CIR’s Eyes on Russia project, has revealed a concerning trend: these drone attacks appear to be systematically targeting civilian buildings and vehicles in an attempt to hinder movement near the frontline.

The team compiled and analysed over 100 drone attacks against vehicles and residential buildings in Beryslav between September 2023 and July 2024, resulting in nearly 130 civilians reportedly injured and 16 dead. Details of the attacks, and where possible, the available imagery, were gathered from Ukrainian authorities, survivors’ accounts, and Russian Telegram channels.

The open source data points to three Russian units stationed on the eastern bank of the Dnipro River, who have been photographed and filmed operating drones carrying explosives and targeting the area.

DW’s Julett Pineda and CIR’s Rollo Collins shed light on how they analysed the incidents and traced the digital clues to the units likely responsible.

Kherson was liberated from Russian occupation in November 2022, forcing the Russians to retreat to the eastern bank of the Dnipro River

A concerning trend

Beryslav was occupied by Russian troops at the beginning of the full-scale invasion, but has remained under Ukrainian control since November 2022. The majority of the city’s pre-war population has fled, meaning those who remain are mainly the elderly or disabled. At least 34 of the reported civilian casualties logged by DW were 61 years old or older when they were killed or injured, and the eldest casualty recorded was a 94-year-old woman.

According to DW journalist Julett Pineda, there are “several hypotheses” for Russia’s targeting of civilians in Beryslav.

“One of them is that these attacks are a form of retaliation against the local population after Ukrainian forces recaptured the west bank of Kherson in the fall of 2022.” The other, she says, is that “Beryslav could have been used as a testing ground for the development of a new Russian drone”.

Rollo Collins, an investigator on CIR’s Eyes on Russia project, had also noticed a trend of drone attacks causing civilian harm in Beryslav and joined DW’s investigation in May.

He says that while drone strikes against vehicles have been “ubiquitous” since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Eyes on Russia’s monitoring reveals that the targeting of civilian-presenting vehicles, or civilians themselves, appears to be limited to Beryslav and the broader Dnipro front, which runs along the river between Kherson City and Beryslav.

“In Beryslav, the strategic logic of Russian units appears to be ‘assume every vehicle is supporting Ukrainian military operations’, even if it’s quite clearly not,” Collins says.

“There were a few instances where what were clearly elderly and immobile civilians were heavily injured by these drones,” he continues. “In another case, we saw what appeared to be an aid truck targeted as it transported water to civilians.”

The aftermath of a drone attack which hit a reported aid truck in May 2024. Source: Telegram

Footage of the attack was uploaded to Telegram by a pro-Russian military blogger, alongside a claim that the truck was carrying “military cargo”. While no casualties were reported in that attack, this is not the first time aid workers have been targeted in Beryslav. In February 2024, two French aid workers were reportedly killed and four others injured in what Ukrainian officials described as a “massive” drone attack.

Analysing the evidence

DW, with support from CIR, analysed hundreds of videos posted on Telegram by Ukrainian local authorities and media organisations, as well as Russian units or associated individuals who post the footage in a bid to attract volunteers and donations.

Pro-Russian and pro-Ukrainian channels will often post the same footage “with competing narratives”, Collins explains. “We’ll often see the Ukrainians claiming they’re civilians, and the Russians claiming they’re military targets.”

Eyes on Russia’s job is to attempt to verify – or debunk – claims through analysis of any available visual evidence. “We’ll look for civilian-presenting clothing or vehicles, as well as individuals who are notably elderly or immobile,” Collins adds.

Where possible, analysts will try to geolocate imagery to pinpoint the precise location of an attack, which may provide further clues about potential perpetrators or is useful for mapping out incidents and monitoring trends.

However, visual evidence of the aftermath of an attack – in cases where it’s available – can also provide useful insight. These attacks involve grenades, mortars, or small explosives being dropped from a drone. Their explosive mass is smaller and easily identifiable “without having to see the video of the drop itself”, explains Collins, adding that they leave behind a “unique and obvious fragmentation signature”.

Screenshot of footage of a drone attack on a vehicle in Beryslav, with the fragmentation signature typical of drone-dropped ordnance visible. Source: Telegram

Attributing responsibility

With support from CIR, DW was able to geolocate seven drone attacks that targeted civilians in Beryslav and its surrounding villages and settlements.

“The opposite bank is under the control of Russian troops,” Pineda explains. “So we knew that Russians launched these drones from the eastern bank.”

Using Google Earth, DW drew the potential flight trajectory the drones could have followed – taking into account their average ranges – to narrow down the area where these attacks might have originated.

“A drone flight range varies depending on the model, battery or the payload’s weight,” adds Pineda. “On average, most of the consumer drones used by these troops can fly up to 15 kilometres.”

Most of the drones used in these attacks are reusable and have munition release mechanisms that usually return to the operator after discharging the payload. Based on this, DW set the range to 7.5 kilometres. This showed that the probable area of deployment from these drones were the twin Kakhovka and Nova Kakhovka cities, both of which are under Russian occupation.

The team of journalists then cross-referenced this information with the Ukraine Control Map, an initiative by OSINT community hub Project Owl, to see who was operating on the other side of the river.

The area where the drones are estimated to have originated. Several Russian units are deployed in Kakhovka and Nova Kakhovka, located on the eastern bank of the Dnipro River. Source: © Google, Maxar Technologies, CNES/Airbus | graphics by DW

“We found three units that have been targeting Beryslav with drones and are stationed in this area,” Pineda says. “In the case of two of them, we’ve found numerous videos posted on Telegram showing them using drones to attack what they claim are military targets in Beryslav city, including civilian vehicles.”

These units have been in the area since spring 2023 or possibly late 2022. While not possible to definitively prove who ordered and carried out the attacks on civilians and civilian infrastructure in Beryslav, findings point in the direction of the 10th Special Purpose Brigade, the 205th Motorized Rifle Battalion and BARS-33 units, with DW able to verify that these three units have operated drones in the area.

Combining open source with traditional journalism

While videos posted online have brought these attacks to light, actual figures “are likely much higher” says Pineda, with incidents often going unreported if no casualties are claimed.

On-the-ground reporting played a critical role in the logging and verification of cases. DW’s Kyiv team got as close to Beryslav city as possible to conduct dozens of interviews with prosecutors, relief workers, volunteers, police officers, and survivors.

“We interviewed a couple whose garage was targeted by a Russian drone,” Pineda says. “The first kamikaze [drone] failed to hit their car. The following day, more drones came and successfully crashed into their vehicle.”

Pineda also points out that with attacks taking place so close to the front line, it’s difficult for local authorities to mobilise to the scene or investigate further. There’s also a risk of double-tap attacks, which have been common in the war.

As a result, the videos DW and CIR have collected from Telegram, at times showing units conducting drone strikes in Beryslav, enabled the teams to uncover a trove of information. It’s what Pineda describes as a “digital footprint” that leads to several Russian units – and she says it could provide “critical evidence” in future prosecutions and accountability efforts.

DW’s documentary, ‘Targeting Civilians: How Russian Drones Terrorize a Ukrainian City’, which provides further detail on this investigation, can be found here.