“Conditions in Myanmar have indeed gone from bad, to worse, to horrific for untold numbers of innocent Myanmar people”.

Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, Thomas Andrews, statement at the Human Rights Council’s 51st session on 21 September 2022.

Figure: Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, Thomas Andrews, statement at the Human Rights Council’s 51st session on 21 September 2022.

Violence in Myanmar has rapidly escalated since February 2021, when the Myanmar Military seized power in the country.

The military’s control of power is not new in Myanmar, which, aside from a short five year window of democracy, has been run for the last 50 years by its army. For that five-year window, a balance of shared power was met between the army, and popular leader Aung San Suu Kyi. When she won votes in 2020’s landslide election, the army arrested Suu Kyi and many of her party, took control of the country, and attempted to squash any form of dissent.

The person at the top who ordered the coup and the full-scale operations against civilians and pro-democratic groups is the leader of Myanmar’s military and its political arm, the Security Administrative Council (SAC), Senior General Min Aung Hlaing.

This crackdown has escalated from violence against protestors and shooting people in the streets to an all-out war in Myanmar with villages and homes being targeted in widespread burnings, torture, airstrikes and more.

Since the coup, this escalation of violence has resulted in the death of more than 2,400 people, as reported by Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP).

The statistics show a grim picture, with more than 12,000 detained, more than 120 sentenced to death, an estimated 18,000 civilian properties destroyed and nearly one million displaced persons, since the coup.

The military’s tactics, strategies, and methods in both stages of this conflict match: burning of homes, targeting of communities in areas where dissent is present, internet shutdowns, rape, torture, and targeting of supplies critical to communities. The indirect result is the mass displacement of civilians. In 2017-2019 it was the Rohingya population – only a few years later the displaced are Burmese civilians.

Myanmar Witness, along with other efforts from civil society, have gathered, documented and verified evidence showing in forensic detail, the widespread pattern of major crimes against humanity.

Open source data and verification gives a unique overview of the conflict in Myanmar. This report maps out verified evidence and credible open source reporting of atrocities against civilians since the coup last February. It shows a dramatic escalation over time in violence and human rights abuses.

Executive Summary

This report maps out verified evidence and credible open source reporting of atrocities against civilians since the coup last February. It shows a dramatic escalation over time in violence and human rights abuses.

The country-wide effort by the SAC to break the democracy movement has led to increased levels of violence and resulted in the pro-democratic movement growing stronger, gaining more followers, support and fighters on the ground.

Open source data and verification gives a unique overview of the conflict in Myanmar. Through the analysis of footage uploaded to social media, as well as satellite imagery and other available data, Myanmar Witness has been able to document how the conflict has spread geographically, drawing in an increasing array of armed groups and actors.

Immediately following the coup, peaceful protests in urban areas were met with worsening violence. In five separate incidents investigated by Myanmar Witness, more than 100 people were detained and more than 310 were killed.

As protests moved out of the cities so did retaliation against civilians. Open source data collected and verified by Myanmar Witness confirms that a step change in military operations led to the destruction of many homes in Myanmar’s northwest.

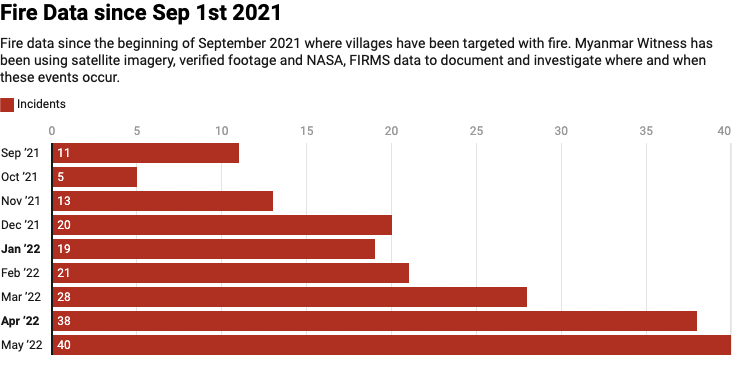

Deliberately setting fires in villages to suppress opposition has risen steadily, month-on-month. In the eight months leading up to May 2022 over 200 fires had been verified by Myanmar Witness. People, as well as their properties continue to be set alight in horrific incidents.

While the burning and other atrocities continue, the use of airstrikes appears to mark the latest evolution of the conflict. The use of airstrikes on civilians and civilian infrastructure, once unprecedented, is now common. The Myanmar Witness arms and investigations teams regularly verify the use of military aircraft in civilian areas, evidence of destruction which indicate aerial assault, and the delivery of combat aircraft from Russia. Russia’s ongoing supply of helicopters and aircraft, for the transport of troops and launching airstrikes, have become a critical enabler of Myanmar’s current military operations.

After 18 months of escalating violence and the emergence of a clear trend of ongoing atrocities, on 25 July 2022, Myanmar’s SAC gave the order to execute four democracy activists. This development raises concerns for the lives of many pro-democracy activists still behind bars. It also shows how SAC continues to respond to dissent.

What began as suppression of protests has become a situation bearing the atrocities of a civil war waged by an authoritarian power with little regard for its people. At each point in this escalation of violence, civilians are bearing the biggest toll, at the hands of the Myanmar military.

Increasing violence against protestors

Immediately following the coup, peaceful protests were met with worsening violence by Myanmar’s security force in major cities, including Yangon and Bago. In five separate incidents investigated by Myanmar Witness, more than 100 people were detained and more than 310 were killed.

February 2021 – Mass arrests in Yankin, Yangon (100+ detained)

In the period following the military’s takeover, peaceful protests erupted on the streets throughout Myanmar – the largest and loudest in Yangon, the heart of dissent.

For just over a week, protestors marched the streets chanting pro-democratic slogans, holding sit-ins and painting murals on the streets (which are still visible from space).

Figure: Satellite imagery from Google Earth over Yangon between February – April 2021 shows numerous murals painted on the city’s streets.

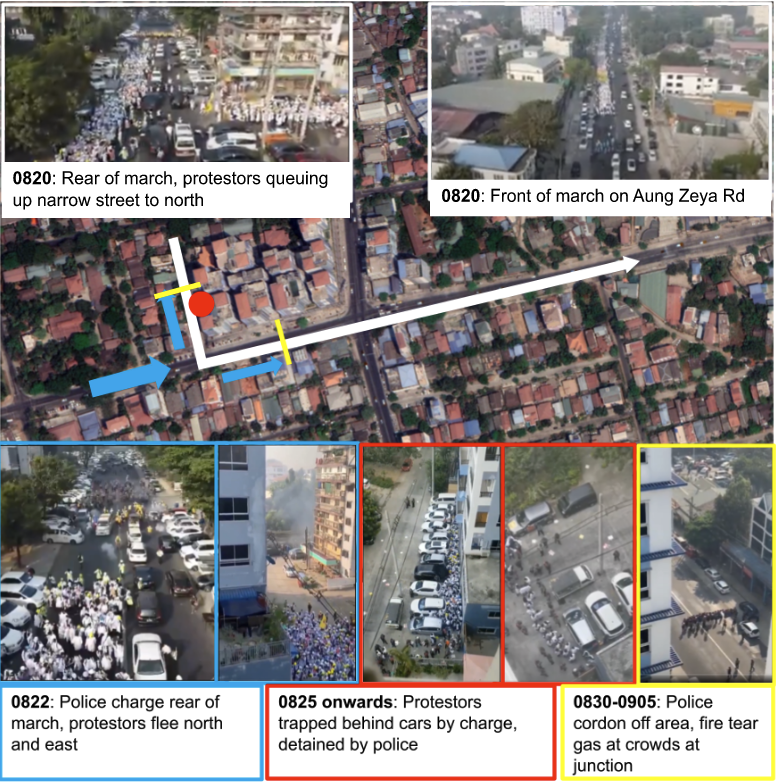

On 28 February, a ‘White Coats Protest’ of several thousand doctors, nurses and students from the city’s universities gathered in Yankin (ရန်ကင်). Police charged the rear of the protest as it began and detained many of the white coat protestors.

Footage verified by Myanmar Witness shows over 100 protestors being detained. Irrawady put the total number of detainees on the day at close to 200.

Figure: Overview of events in Yankin on 28 February 2021.

March 2021 – Protestors killed in North Okkalapa, Yangon (30+ killed)

In the weeks after the coup, there was a gradual increase in the level of violence used by Myanmar’s police and military against protestors. Mass arrests began and live ammunition was being used against peaceful protestors.

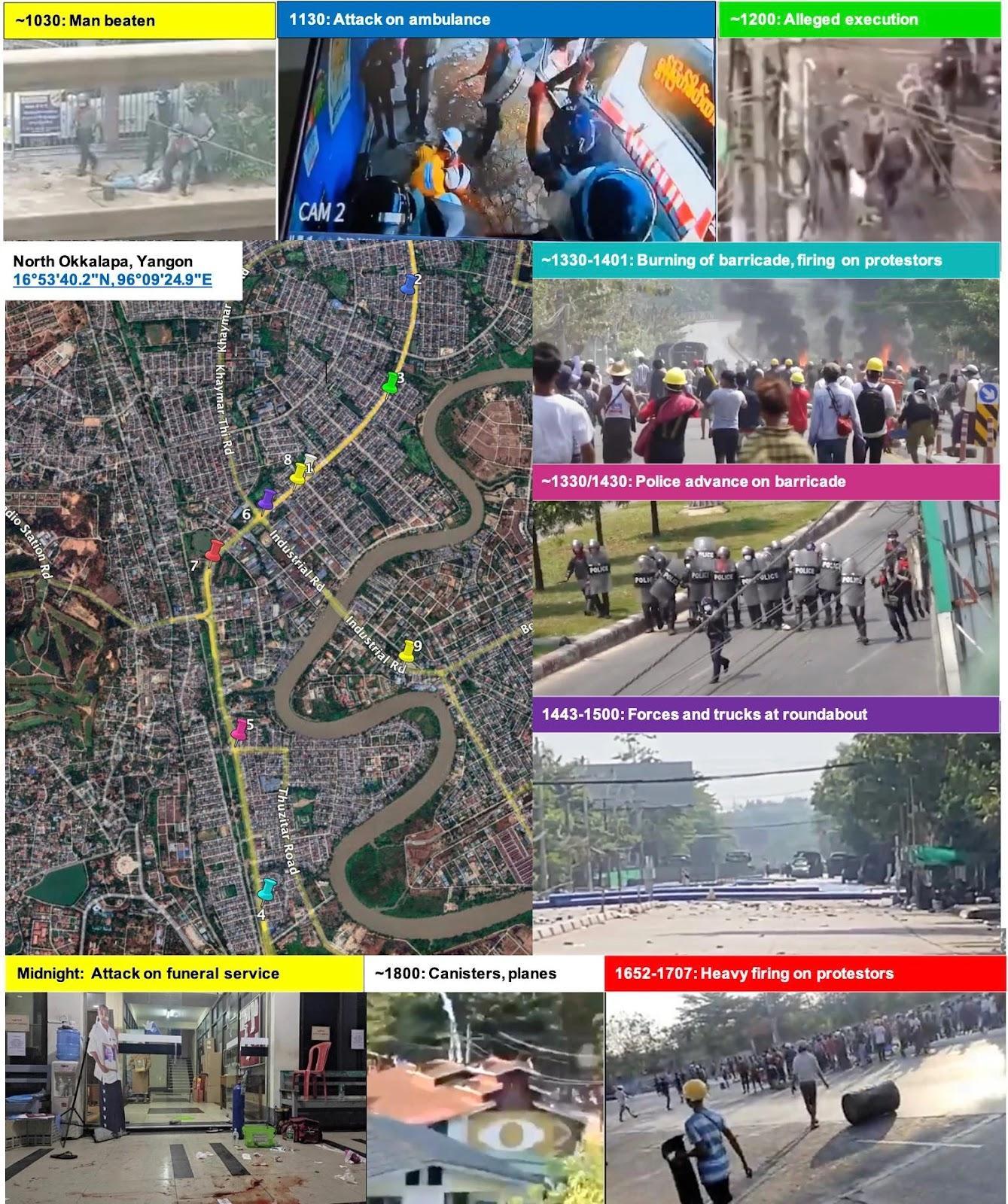

The 3 March 2021 marked a tipping point. A large protest in Yangon’s working-class suburb of North Okkalapa (မြောက်ဥက္ကလာပ မြို့နယ်) became a turning point for the military’s use of violence against civilians.

Analysis by Myanmar Witness (Violence against protestors in North Okkalapa), which documents the events in North Okkalapa, shows how two protests merged in the middle of a major road called Thudhamma Road.

Just after 1030 in the morning, protestors were attacked by Myanmar security forces. Large numbers of demonstrators were detained and hauled into police vehicles. This analysis, coupled with media interviews from those on the ground, identified many of the forces as soldiers from the 77 Light Infantry Division (LID) – known for committing human rights abuses in the past.

Figure: verified timeline of events that took place in North Okkalapa on 3 March 2021.

While North Okkalapa was the strongest example of the crackdown on this particular day, it was not the only place this level of violence was witnessed.

On the same day in other towns and cities across Myanmar, violent methods were also seen. For example, in Monywa our team verified graphic footage of Myanmar police officers dragging away the bodies of civilians that had been killed during protests.

Our investigation shows that live ammunition was used against protestors, and that there was a widespread effort to kill civilians that took part in pro-democratic protests. This was the start of what was to become a grim period of killings and attacks against the civilian community in Myanmar.

Figure: Our analysis documenting just one of the victims from 3 March in North Okkalapa.

Protests in other parts of Myanmar on 3 March also witnessed the same heavy handed response from Myanmar’s security forces. In Mandalay, live ammunition was used to suppress young protestors that took to its streets. During that protest, Ma Kyal Sin (also known as Angel) was shot in the head.

Figure: Breakdown of the geolocation of user-generated content concerning Angel.

The widespread crackdowns on peaceful protests and increase in violence during this period signalled a shift in the military’s policy towards the pro-democracy movement. In the weeks following 3 March, hundreds were killed. This number includes 43 children.

During this same period, soldiers started to defect and flee the military. People started to leave the cities where they were actively taking part in the protests, and instead join camps in Myanmar’s remote jungle areas to learn basic guerrilla warfare techniques. The most popular group that quickly grew in its ranks is the People’s Defence Force (PDF).

From the high level scale of violence exhibited by the Myanmar military and police against protestors, there is a clear cause and effect relationship showing how that violence resulted in the increase of once peaceful protestors to training for conflict against the Myanmar military.

March 2021 – Protestors killed in Hlaing Tharyar, Yangon (40+ killed)

Hlaing Tharyar (လှိုင်သာယာ) was reported to be the site of large, well-organised protests against the military coup in Myanmar. The area was a hotbed of resistance, and resulted in one of the worst crackdowns seen in post-coup Myanmar.

On 14 March, when the biggest protest took place, more than 40 protestors were killed. There was no indication they were armed or violent. Our analysis (Violence Against Protestors at Hlaing Tharyar) shows how police openly posted on social media about the type of guns they were going to take to Hlaing Tharyar, and how they and LID 77 “are going to fuck Hlaing Tharyar for sure”.

Our team identified those making the comments as members of the Lon Htein police. This shows the mentality and approach to pro-democratic protestors at the time, across security services, from military to police.

Figure: Screenshots of aLon Htein police officer’s Tiktok account and selfies/images featured.

March 2021 – Myanmar’s ‘Bloodiest Day’ (160+ killed)

Known as one of the bloodiest days in the crackdown on protests, 27 March saw activity by Myanmar’s security forces extend to other parts of the country.

Prior to this day, violence had been concentrated on protestors in Yangon. However, on 27 March, more than 70 of the victims were killed in the Mandalay region alone.

The day also marked the Myanmar military’s annual Armed Forces Day holiday with a parade in the country’s capital Naypyidaw (နေပြည်တော်).

It was during this timeframe that Myanmar Witness started to identify targeted attacks on civilians by security forces. For example, in an event verified by our analysts, soldiers driving on a main street in Dawei (ထားဝယ်) shot at a motorbike passing by, and then pursued those who fled the scene.

Figure: shooting of a civilian passing by a military vehicle in Dawei, 27 March 2021.

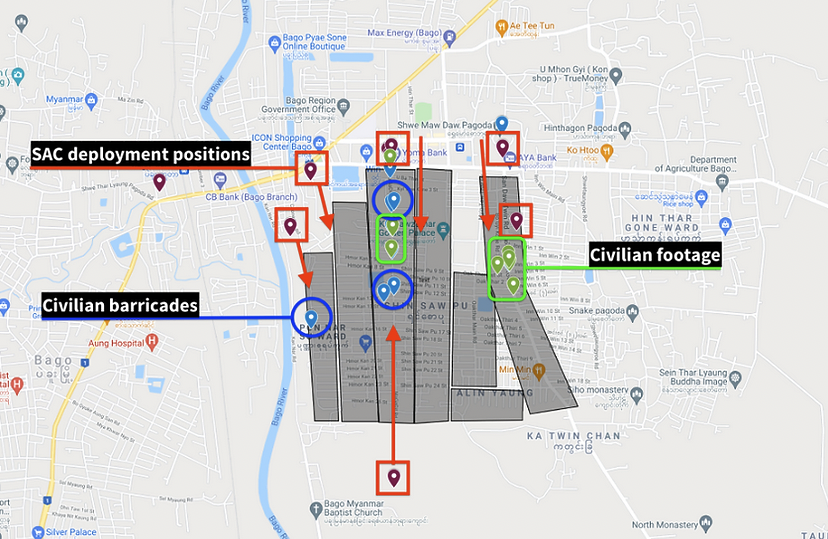

April – Protestors shot in Bago (80+ killed)

In another mass crackdown on protestors, analysed by Myanmar Witness, more than 80 protestors were killed on the streets of Bago (ပဲခူးမြို့) by local security forces, namely the 77 LID.

The Myanmar military used even more dangerous tactics against protestors in urban areas, including explosive ordinances.

Figures: Images from social media of what appears to be RPG rounds in Bago from 9 April.

The event was also the stage for new strategic methods to suppress protests, by deploying military squads at multiple exits to corner, block and shoot at protestors.

To document the attack on protestors, Myanmar Witness analysed 71 separate pieces of verified data to build a thorough picture of what happened on the ground. This included videos and images, social media posts and comments, and privately submitted information collected by Myanmar Witness, triangulated with witness statements collected by the Washington Post and NHK News.

The map below indicates the locations where the majority of protestors were gathered, before they subsequently turned and ran south as security forces (marked in red) advanced. The blue markers indicate the known locations of barricades constructed by the demonstrators. The grey shapes indicate the wards.

Figure: Visualisation of the material collected by Myanmar Witness indicating the locations of footage and imagery in green, protest barricades and street blocks in blue, and the deployment of SAC forces on 9 April in red boxes. The red arrows indicate the SAC’s direction of travel.

When analysed together, the footage suggested a strategy by security forces to attack the demonstrators from the north, and move them south down both Maga Dit and San Daw Twin Roads. As they fled south, a unit deployed at the south of Mada Dit Road moved north, effectively trapping the demonstrators. This ‘boxed’ in protestors, forcing them to flee east into the parkland and suburban area between the two main roads.

The proliferation of clearance operations

As protests moved out of the capital so did retaliation against civilians. The rise of the PDF and its resistance led to violent clashes, including at a Myanmar Police outpost in Myanmar’s north. Open source data collected and verified by Myanmar Witness confirms that a step change in military operations led to the destruction of many homes in Myanmar’s northwest.

May 2021 – Outpost attacked and retaliation on civilians

One of the first flashpoints in the conflict was an attack on a Myanmar police outpost in Myanmar’s north. The Moebye (မိုးဗြဲ) Police Station was a defended position within an area that had seen a rise in small clashes between the military and local PDF groups.

The attack is reported to have been a retaliation for a police raid on a funeral just days earlier. The police detained eight people at the funeral.

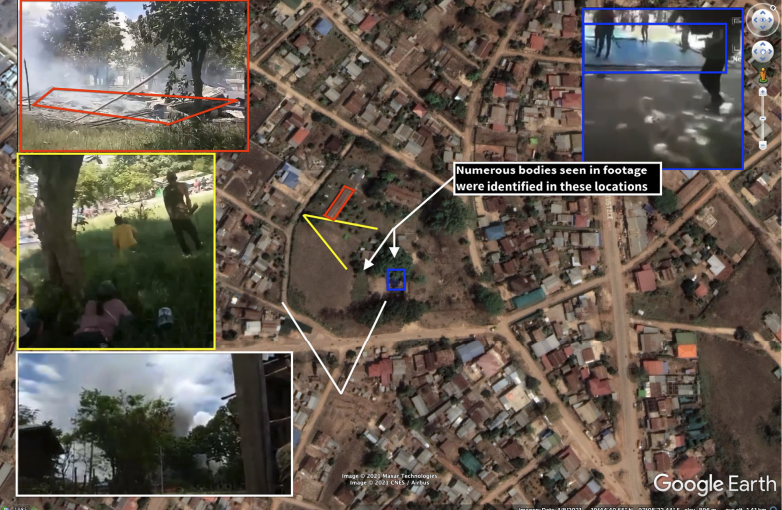

After a three-hour battle, PDF groups reportedly broke through the police station’s defences and overran the station. We collected graphic footage of trenches (available on request) lined with bodies of police officers, and other evidence of a pile of bodies close to the station’s headquarters.

This attack on the outpost marked a critical moment in the conflict. It showed that PDF groups were able to plan, organise, and overrun Myanmar security forces facilities.

Figure: Myanmar Witness geolocation of bodies filmed after the storming of Moebye police station.

The attack was a turning point in how the Myanmar military approached protecting civilians in their operations. Their response was to shell numerous buildings in Moebye, destroying surrounding areas and target homes, resulting in mass deaths and displacement.

In the days after the attack, local media (Irrawaddy, Myanmar Now) reported that the military had imposed daytime curfews in Moebye and Loikaw. Myanmar Now reported that about 50 youths were arrested and released after questioning about the attack. The report also claimed that more than 10,000 villagers from the surrounding area fled their homes and that many inside Loikaw were unable to leave due to the military operation against PDF fighters in response to the storming of the police station.

One resident said: “Some people don’t want to leave, but those who do can’t anyway, because there’s no way out. They’re afraid they’ll be shot at if they try to leave” (Myanmar Now).

A number of social media claims of civilian homes hit with artillery have been identified, however remain unverified due to lack of updated satellite imagery. A series of images uploaded by Irrawaddy from 25 May also shows the destruction of a farmhouse in Loikaw due to shelling. These images are unverified, but remain consistent with numerous other claims of shelling in the area.

June 2021 – Homes destroyed, Kinma, Magway (150+ homes)

In one of the first events of its kind since the February 2021 Coup, reports emerged in mid-June of hundreds of homes in a village in Myanmar’s north being burned down.

Analysis by Myanmar Witness identified heat signatures from Kinma village (ကင်းမ) on 15 June and verified the destruction to the village using satellite imagery, coupled with images taken on the ground.

Figure: Satellite imagery from Maxar and social media footage showing destruction to Kinma Village.

The village was estimated to have contained between 230 and 250 houses with a population of around 1,000 people (BBC, Myanmar Now). Images geolocated by Myanmar Witness to the village show widespread destruction of homes (Twitter user), with some areas reduced to ashes (Facebook user). Locals reported that around 200 houses were destroyed (Myanmar Now, DPA). A manual count of the destroyed blocks seen on satellite imagery indicates there were at least 154 blocks destroyed, however there may have been more than one house in each block.

According to media interviews with locals, at least two elderly residents were killed in the fire (Myanmar Now, DPA). These have been named on social media as U Mya Maung and Daw G Mei (Twitter user, YouTube User). Further social media posts include claims that:

a local person was shot in the leg by an SAC soldier;

four elderly people were killed in the fire (Twitter user, YouTube user);

two individuals were taken away by SAC forces and one returned unconscious (Twitter user);

that multiple livestock were killed (Twitter user).

July 2021 – Mass graves in Myanmar’s north (40+ killed)

A clear increase in violence was identified in the north of Myanmar as armed opposition emerged, especially in the Sagaing region.

One of the more shocking events, which gives an insight into the mentality of forces operating in the area, was the discovery of 40 bodies buried in mass graves in Sagaing’s Kani Township (ကနီမြို့နယ်). Many of the bodies had hands bound and displayed signs of torture before either being burned or buried in shallow graves.

Figure: In the above image on the left, after one body was removed from one of the shallow graves, another set of feet and legs can still be seen in the grave. On the image on the right, hands can be seen crossed over each other with fabric that has been used to tie them together.

Analysis by Myanmar Witness, in collaboration with the BBC, indicated how villagers were rounded up, separated by gender and killed.

The killings took place in July, in four separate incidents in Kani Township. The area was an opposition stronghold in Sagaing. Reporting claims that the killings were a punishment for attacks by pro-democratic militia groups.

Fire as a strategy of war

A deliberate strategy of setting homes alight first emerged in June 2021 in Kinma. Since then, the use of arson to suppress opposition has risen steadily, month-on-month. By May 2022 over 200 fires had been verified by Myanmar Witness.

Horrific incidents of people being burned alive, or their bodies cremated, have emerged and been confirmed by Myanmar Witness during the course of the conflict. During two incidents in December 2021, more than 46 civilians were killed and set alight.

September 2021 – defensive war

On 7 September, the exiled National Unity Government (NUG) announced a defensive war in Myanmar, calling for civilian militia to fight the military and its assets.

Acting NUG president Duwa Lashi La called upon groups to target “the military junta and its assets” and to “carefully protect the lives and properties of the people” while observing codes of conduct.

Militia groups were urged to target the junta’s leader, Min Aung Hlaing, and the military council in different ways, and to maintain control of their areas.

Duwa Lashi La also stated “from today onward, all the civil servants under the military council, we warn and forbid you from going to the office”.

In the proceeding weeks after the call for a defensive war, clashes escalated between PDF and Myanmar military forces, most noticeably in the country’s north resulting in losses on both sides. These events are important to follow, as they indicate the pro-democratic forces increasingly taking up arms and countering the military’s control in certain areas.

The use of fire against homes

September also marked a commencement of an observed trend in the use of fire against communities as tracked and analysed by Myanmar Witness. This trend would go on to become a significant part of the conflict.

Between September 2021 and May 2022, more than 200 villages had been targeted with fire, primarily in the north.

Figure: Myanmar Witness verified incidents where fire has been used against villages and towns from September 2021 to May 2022 – as documented in our analysis on the trend of fires in Myanmar. Full graphic availablehere.

September 2021 – Thantlang

An example of this trend is the destruction to Thantlang (ထန်တလန်မြို့) in Chin State. The town was first targeted on 18 September and would see homes burned on more than ten separate occasions.

Local media reported that arson and artillery attacks were used by Myanmar military forces on Thantlang. Locals speculated that the motivation was a loss of a local military base to the Chinland Defence Force – Chin National Army alliance (CDF-CNA) (DVB English). Local media also claimed that a local pastor (Cung Biak Hum) was shot and killed by soldiers while he was attempting to put out the fires (Myanmar Now).

Footage seen on YouTube, uploaded on 18 September, was geolocated by Myanmar Witness to the town. The aftermath of the area can also be seen on Facebook here and here. One of the images, made as a panorama, illustrates the scale of the damage.

Figure: Destruction in Thantlang Township.

October – ‘Clearance Operations’ in Myanmar’s north

The Myanmar military launched “clearance operations” in October to counter resistance groups and continue its ruthless crackdown on those defying military rule.

With the launch of those operations came further deployments of troops and an increase in clashes and atrocities in the north.

Analysis by Myanmar Witness showed that these operations led to a significant increase in towns and villages being targeted with fire, similar to what was seen in the clearance operations waged in Rakhine State against the Rohingya population. Footage verified by Myanmar Witness, seen below, shows an example of just one of the villages destroyed in Chin State in October 2021.

Figure: A large convoy can be seen in this footage, while a fire burns.

Across Myanmar’s north, potential crimes against humanity and war crimes were waged upon civilian communities that were suspected of supporting pro-democracy groups. Much of this has been documented in the analysis of Mass Killings in North-West Myanmar.

By November clashes in every region and state of Myanmar were being reported in the country.

December – Civilians burned and killed (46+ burned bodies)

Clashes and the burning of villages continued in Myanmar’s north. In at least two events in December, reportedly linked to the Myanmar military, people were allegedly burned alive.

One of these events was in Done Taw (ဒံးေတာ) in Sagaing on 7 December 2021. Locals interviewed by Myanmar Now stated that military soldiers entered the village from near the Pathein-Monywa road at 0800.

According to villagers and a local PDF leader (reported by Myanmar Now and The Irrawaddy), 11 villagers were reportedly captured, set on fire, and burned to death.

A video uploaded to social media by various media outlets shows the aftermath of the attack, including the burnt remains of bodies (graphic footage – available on request). The video’s voiceover states: “They were shot and stabbed while forced to kneel, with their hands tied”.

Myanmar Witness verified the location where these bodies were found to be just outside of Done Taw village, in farmland located at 22.142916, 95.062057.

Figure: Geolocation of the original Done Taw video, from a background landscape. Further documentation on this event can be found in this report.

Another significant event involving the use of fire against more than 30 civilians was in Moso (မိုဆိုရွာ), Kayah State, on 24 December 2021.

Myanmar Witness documented multiple images and pieces of footage which showed numerous vehicles containing severely burnt bodies. Local reports indicated that there were at least 35 bodies found at the scene along with eight vehicles and five motorbikes. As well as two Save the Children employees, reports by Myanmar Now indicate that children were amongst the deceased.

Our investigation into the alleged killings, including the verification of this event, and analysis of footage from the scene, shows individuals walking away from the burning vehicles, potentially in the direction of two military bases.

Figure: An image demonstrating a lack of physical evidence to claim accidental fire damage in the aforementioned Kantarawaddy Times picture.

The air war

As the conflict has developed, the tactics have shifted. The use of airstrikes on civilians and civilian infrastructure, once unprecedented, is now all too common. The Myanmar Witness arms unit has regularly verified the presence of military aircraft in civilian areas, destruction which bears the hallmarks of an aerial attack and also the delivery of new shipments of arms from Russia.

The trend in airstrikes

Many aerial attacks have occurred in civilian areas. They have resulted in the deaths of civilians, including schoolchildren, and damage to homes, schools and monasteries. In-depth research has identified 16 ‘unlawful’ air attacks between March last year and August this year, including two airstrikes which used cluster munitions.

Myanmar Witness has tracked events around a symbolic ‘peace town’ which was one area repeatedly targeted with aerial attacks, destroying homes and displacing thousands – many of whom waded across the Moei river to cross the border into Thailand. Aerial attacks continued later in April and led to further destruction of the town, reducing the chances that families can return home anytime soon.

Figure: Video uploaded by Cobra Column of explosions, verified and geolocated by Myanmar Witness to Lay Kay Kaw (လေးကေ့ကော်) (see report: Airstrikes on residential areas in Lay Kay Kaw).

While a number of these aerial attacks reportedly happened in 2021, there appears to have been an increase in both the targeting of civilian areas and significant strikes on areas where casualties had been reported in 2022.

At the start of 2022, over just 6 days in January, numerous air strikes were reportedly carried out in Myanmar’s north, many resulting in civilian injuries and deaths:

– 8 January – 10 airstrikes were reported in five hours on Loikaw, Kayah State.

– 10 January – Helicopter gunships attack a village in Sagaing.

– 11 January – Six people reportedly killed in Loikaw, Kayah State by aerial bombing.

– 12 January – 10 people killed by an airstrike in a village in Sagaing.

– 16 January – Refugee camp in Kayah bombed killing six.

September and October 2022 – the bombing of a school and concert

Airstrikes have continued throughout 2022, causing many civilian deaths, including an attack on a school in September, which is the subject of a forthcoming report by Myanmar Witness.

Recent figures suggest that during October 2022, the military carried out 28 airstrikes around Myanmar. A number of journalists believe that airstrikes have peaked due to setbacks in ground operations, though they have also been linked to the end of the rainy season.

Myanmar Witness documented a strike in October on a commemoration gathering in Kachin State near Hpakant (ဖားကန့်) which reportedly killed 80, showing the devastating impact airstrikes can have on civilians.

Since the incident, the military has claimed that the area was used for military activities by the Kachin Independence Army (KIA); specifically, that A Nang Pa is the KIA Brigade 9 Headquarters. However, as well as only two of the casualties sporting military fatigues, Myanmar Witness has discovered additional information which suggests that the victims were not part of a militia group, instead that they were attendees of a golf tournament which was occurring in this area.

Figure: Planet satellite image from 26 October, 2022 showing destroyed buildings and area at site of concert bombing in Kachin State.

Russia as an enabler

While the Myanmar military is responsible for the conflict’s latest evolution, it is being fuelled by deals with foreign entities for air assets, arms and fuel.

Since the Coup, Myanmar Witness has been monitoring the deepening diplomatic, financial and military ties between the Russian Federation and the SAC. Given the tight western sanctions on both Myanmar and Russia, the symbiotic nature of this relationship between the two pariah states is both unsurprising and alarming. The growth in investment and trade between the two regimes, paired with the frequent diplomatic visits, has undeniably led to increased suffering on the ground.

An in-depth investigation by Myanmar Witness found that between 2015 and 2019, 12 Russian-manufactured Yak-130 aircraft were delivered following purchase agreements between Myanmar and Russia. Following the coup in 2021, Russia expressed an intent to continue its support for the Myanmar military and to supply further Yak-130 jets. On 15 December 2021, six additional jets were unveiled at Meiktila (မိတ္ထီလာမြို့) airbase, Myanmar, as part of the 74th anniversary ceremony of Myanmar’s Air Force (MAF).

These sophisticated two-seater jet trainers have ground attack capabilities and Myanmar Witness has verified footage of the Myanmar military using the jets to fire unguided rockets and 23mm cannon fire in and around civilian-populated areas. These aircraft make up a significant proportion of the 100 combat-capable aircraft that Myanmar is reported to have and include helicopters, such as the Russian-made Mi-35 which can both transport ground troops and conduct airstrikes.

Figure: 1st and 3rd images show a Yak-130 in flight over Loikaw area, Kayah State, on 21 February 2022, in confidential footage shared by The Free Burma Rangers and analysed by Myanmar Witness. The central picture is for reference purposes. Source:Aviation News Youtube.

Earlier reports by Myanmar Witness also verified the shipment and presence of Russian-manufactured BRDM-2M 4X4 armoured vehicles and Serbian-manufactured rockets.

On 17 October 2022, Myanmar Witness investigators recorded the first sighting of a Russian-made Su-30 in Myanmar via satellite imagery. While it is difficult to assess how these jets will be used in operations, and far fewer of them have been ordered compared to the numbers of Yak-130 in operational use, they have more than twice the payload of the Yak-130 and thus the capability to harm more people and homes.

The execution of political prisoners

After 18 months of escalating violence and the emergence of a clear trend of ongoing atrocities, on 25 July 2022, Myanmar’s SAC gave the order to execute four democracy activists.

Analysis by Myanmar Witness shows that this was the first judicial executions in Myanmar since 1987. The executions reportedly happened in Myanmar’s largest city, Yangon – the strongest and most vocal area in the pro-democratic protest movement.

This development raises concerns for the lives of many pro-democracy activists still behind bars. It also sets a dangerous precedent for how the SAC quells dissent.

Deepening conflict

Since July, violence has continued and resistance deepened. Fires continue to burn in villages associated with PDF or anti-SAC groups. The SAC continues to look to like-minded nations for weapons and resources, drawing external actors into this civil war. New deliveries of Russian-made Yak-130 jets and Su-30 aircraft have been identified, increasing the risk of continued aerial attacks. Attacks on pro-democracy schools and the politically-motivated mutilation of a teacher, verified by Myanmar Witness, have shocked both local and international communities.

Over time, there has been a significant increase in atrocities committed by the Myanmar military against those who dare to either speak out or take up arms against the authoritarian power.

Undoubtedly, the biggest toll is suffered by civilians. In numerous events documented through the phones and cameras of those on the ground, Myanmar Witness and other civil society organisations have documented and investigated retaliatory, indiscriminate, targeted or careless attacks on the civilian population. As well as the disregard for their safety, the military has targeted the necessities they rely upon for survival.

The world has witnessed this descent into civil war. The violence began at protests on the streets before growing into an active conflict. Fighting is still escalating in the country, and so is Myanmar’s death toll.