During Kamala Harris’s historic Vice-Presidential campaign, she faced a torrent of online abuse and lies that claimed she “slept her way to the top.” Online abusers claimed Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern of New Zealand was secretly transgender. Critics of India’s President Narendra Modi have been targeted by a torrent of hate and even deep fake pornography.

During Germany’s recent election, Annalina Baerbock was subject to far online more harassment than her two male competitors. Other women with public presences are also affected; eight out of ten women journalists surveyed in Brazil “changed their behavior on social networks…to protect themselves from attacks.” Video game streamers have had SWAT teams show up at their doors, called in after online abusers identified their addresses and called in fake threats to their homes. As Liz Truss settles into the role of U.K. Prime Minister, she is undoubtedly facing similar attacks.

These incidents are all part of a broader phenomenon of online gendered abuse and disinformation, which seeks to silence women and keep them out of politics and public life. Gendered disinformation is a “subset of online gendered abuse that uses false or misleading gender and sex-based narratives against women, often with some degree of coordination, aimed at deterring women from participating in the public sphere.”

It affects not only high-profile women, but ordinary citizens weighing whether to take on public-facing positions or make their voices heard, online or off. It perpetuates gender inequality in societies around the world, and is amplified and exacerbated by authoritarians who wish to undermine the democratic project.

I have researched gendered disinformation and abuse since 2017, when women in Ukraine and Georgia told me how, in the course of their democratic activism, they were targeted by accounts that appeared to be Russian in origin. They were sexualised and became the subject of lewd rumors that diminished their intellect, abilities, and fitness for service. In further research, together with a research team at the Wilson Center, I documented how Russia, China, and Iran targeted women journalists with similar narratives in attempts to undermine their credibility and bully them out of reporting the truth about events in those countries.

Gendered abuse and disinformation campaigns are not solely foreign actors’ domain, however. These tactics are also exploited by domestic anti-democratic forces and used as weapons of war. Preliminary findings from a forthcoming study conducted by CIR’s Myanmar Witness project has found widespread politically-motivated abuse of women online. This abuse includes significant volumes of threats, sexualised language and doxxing, or the release of personal information such as addresses and phone numbers. Some of the threats and doxxing activity are linked with subsequent, offline harassment and detentions. Meanwhile, sexualised character attacks against women online were found to be designed to shame women out of public discourse.

CIR’s Afghan Witness project found a significant increase in online harassment and disinformation targeting Afghan women’s rights activists following the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan. Female activism in the form of protests was marked by corresponding peaks in gendered online hate speech, which has grown since the Afghan women’s rights movements have increasingly taken to social media in response to Taliban repression.

Sexualised narratives are used to degrade women’s rights activists, who are accused of being un-Islamic and backed by Western powers. Further, disinformation narratives are designed to discredit women by suggesting they are promiscuous, staging incidents to seek asylum, or that they are paid by foreign actors.

Through this and other analysis it has become clear that gendered abuse and disinformation affects women’s political participation and physical safety on the domestic front. Internationally, it also provides an opening for malign foreign actors to undermine national security and democratic resilience of their adversaries.

The Centre for Information Resilience is launching The Hypatia Project to combat these online harms, expanding on its previous research and analysis.

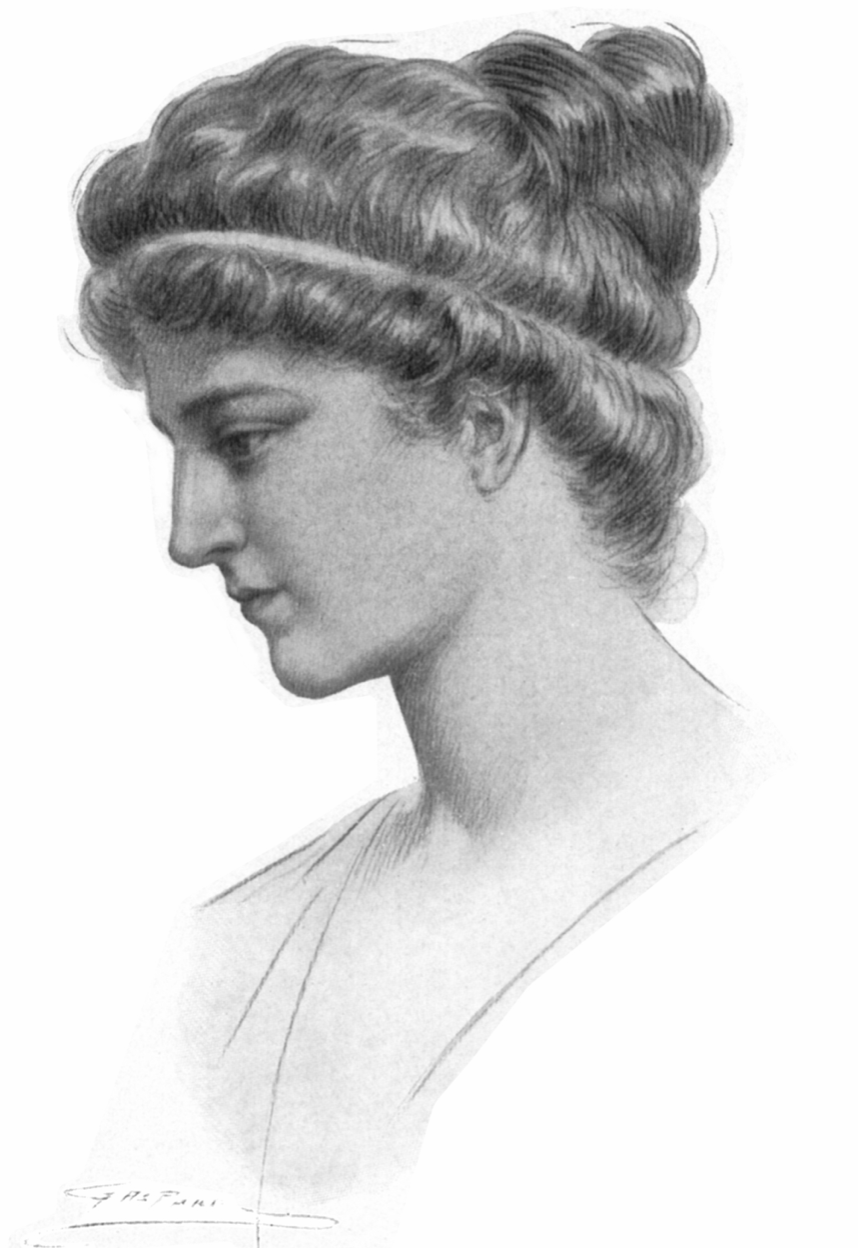

The project is named after Hypatia of Alexandria, one of the first women to study and teach mathematics, philosophy, and astronomy, a highly regarded thinker, and one of the last great scholars of her city before its decline.

During Hypatia’s lifetime, Alexandria was a city rife with religious and political factions, but Hypatia taught tolerance and nonpartisanship. Her wisdom made her a counselor to the city’s leader, and ultimately led to her murder; a violent mob of men pulled Hypatia from her carriage, beat her to death, dismembered her, and burned her remains. According to historians, Hypatia’s demise was a blow to free thought and civil discourse in Alexandria, and the city lost prominence as an intellectual capital soon thereafter.

Hypatia taught in the ancient agora, or public square, and was silenced because of her prominence. In today’s digital public square, online mobs target women and other marginalized groups in attempts to silence them.

Through research and training Hypatia Project at the Centre for Information Resilience seeks to:

further document and understand networked online abuse and the causal link with offline violence, building on work that CIR pioneered in Afghanistan and Myanmar;

equip targets of abuse with the tools they need to stay safe and hold their digital ground, and

advocate for private and public sector policy solutions to make the internet—the modern, global agora—safer and more civil for everyone.

The Hypatia Project’s first public report will further document the relationship between gendered disinformation and coordinated hostile state activity online and will be released this autumn.

To get involved, email [email protected].