Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russia’s attritional fighting has bombarded Ukrainian schools, hospitals and other vital civilian infrastructure in an attempt to make life unsustainable for remaining civilians.

But Russia has waged an aggressive campaign online as well as off, seeking to exploit and exacerbate divisions and tensions created by the war in Ukraine. While the strategies used are not new, the full-scale invasion saw an intensification of efforts to spread fear, muddy the waters, sow division, and ultimately, undermine support for Ukraine.

More than two years on, as more than two billion people across 50 countries head to polling stations in 2024, democracies around the globe are increasingly vulnerable to Russian influence attempts to polarise public opinion, discredit governments, and cast doubt on democracy itself.

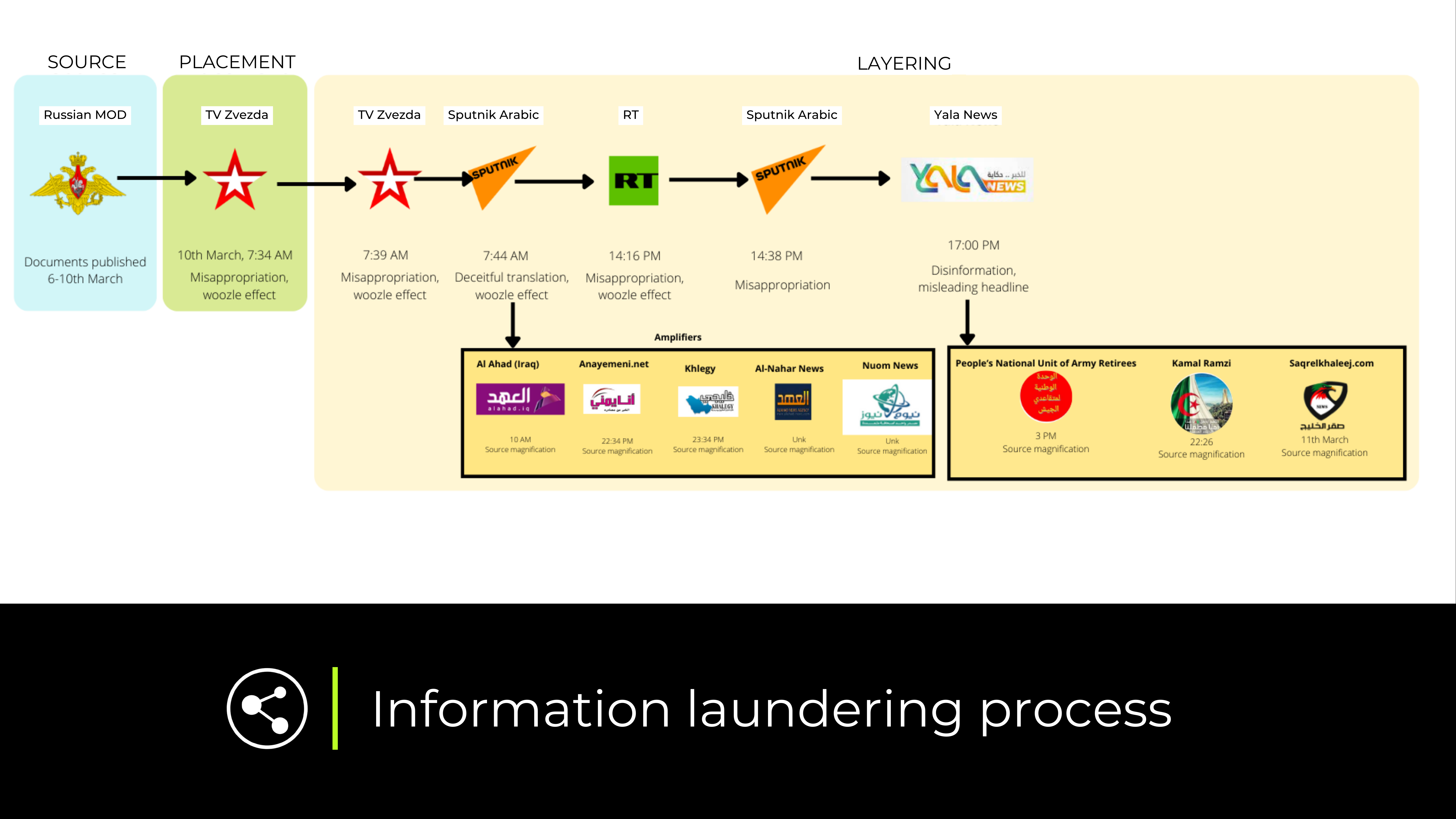

The information laundering process

While we’ve heard plenty about the Kremlin’s narratives and disinformation campaigns – and the bot networks and troll farms behind them – we’ve heard less about the specific strategies that are making dis– and misinformation increasingly difficult to detect.

Key to this process is information laundering. Akin to money laundering, information laundering is when propaganda is spread through layers of media to conceal and distance it from its Kremlin origins. Actors use a range of techniques to build credibility and embed laundered information within public discourse, allowing falsehoods at the fringes of the media environment to go global and shape mainstream narratives.

One of the aims is to subtly manipulate information in a way that makes inaccuracies difficult to detect or debunk. In simple terms, clean and dirty information – or fact and fiction – are washed together until the two become indistinguishable, explains Belén Carrasco Rodríguez, director of CIR’s Eyes on Russia project.

“Information laundering is a multi-layered influence process involving the combination and progressive application of a set of influence techniques that seek to distort an event, a claim, or a fact,” explains Rodríguez.

“Instead of just disinformation, this involves a more complex process where facts are mixed up, decontextualised, misappropriated or misconstrued. Once a fact is recycled through a network of accounts or layers of media, it becomes completely distorted, and the original source is obscured.”

Laundering information involves the gradual application of techniques such as disinformation, misappropriation, click-bait headlines, and the ‘Woozle effect’ – when fabricated or misleading citations are used repeatedly in laundered news items in an attempt to provide ‘evidence’ of their integrity.

The information is then integrated into and spread around the information ecosystem through processes such as smurfing – a term borrowed from money laundering – where an actor sets up multiple accounts or websites to disseminate the information. There’s also what disinformation analysts call ‘Potemkin villages’, a network of accounts or platforms that share and endorse each other’s content, serving to amplify and propagate material.

The goal of such dissemination techniques is to boost visibility while building credibility – based on the premise that audiences tend to trust information more if it’s widely reported by different actors or organisations.

Techniques used during the information laundering process. Source: Nato Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence, 2020.

An international operation

CIR has seen numerous examples of information laundering in different languages and online environments since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. In 2023, our investigators worked alongside the BBC’s disinformation team to investigate Yala News – a UK-registered, Syrian-linked media company that was found to be spreading Russian state disinformation to millions in the Arabic-speaking world.

The topics and rhythm of Yala’s social media posts revealed traits of information laundering, with many of the posts identical to those seen on Russian state media just a few hours earlier.

An example of the information laundering process: from the Russian Ministry Of Defence to Yala News, and the outlets involved in the layering and amplification of stories in between.

Some videos – including one that claims President Zelensky was drunk and ‘lost his mind’ – generated over a million views. According to Rodríguez, such content “hits the right audiences”, allowing outlets such as Yala to not only disseminate pro-Russian, anti-western messages but to drive their readership at the same time.

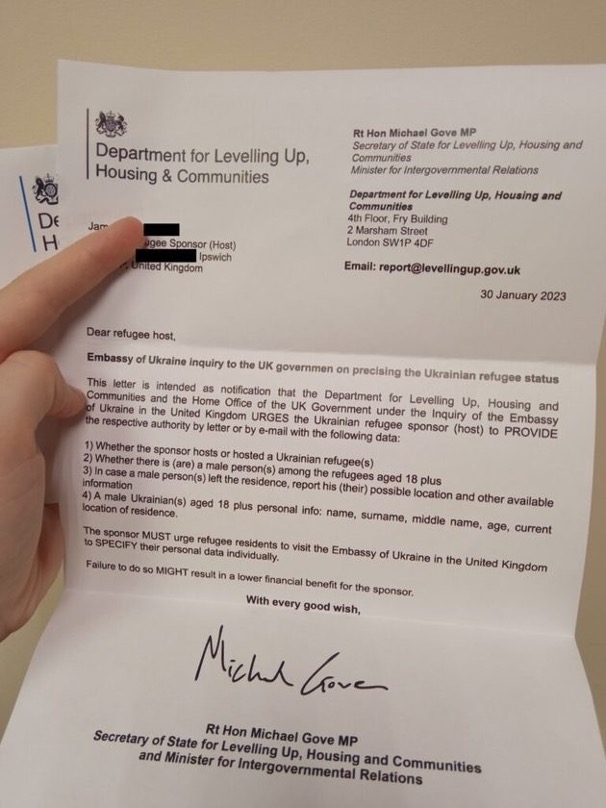

In another case, in February 2023, CIR saw a fake UK government letter circulated online and addressed to UK sponsors of Ukrainian refugees. The letter asked for the personal details of Ukrainian men living in the households, information that had allegedly been demanded by the Ukrainian Embassy in London for reasons unspecified.

It was an operation that Rodríguez describes as hybrid, combining a forgery with an information laundering operation that was designed to stoke fear among the Ukrainian refugee community while portraying the Ukrainian armed forces as desperate and running out of manpower – and prepared to go to cruel lengths to obtain recruits.

The fake UK government letter asking for the personal details of Ukrainian refugees staying with UK sponsors.

Such narratives were embedded into social media groups in countries supporting the Ukrainian war effort, like Lithuania and Latvia, with posts suggesting authorities were collecting information on Ukrainian men so they could be deported for conscription.

“They used that forgery as an initial entry point to a further influence campaign involving information laundering,” explains Rodríguez, adding that the letter was swiftly shared online alongside stories from individuals who had supposedly received it, or knew someone who had. These narratives were an attempt to add legitimacy to the claims, she says.

“This is how laundering works – online and offline networks mobilise to spread a piece of disinformation, in this case, a forgery.”

Sowing division, casting doubt

Like large-scale money laundering operations, it is the transfer of narratives into other countries’ political environments that helps to strengthen their credibility while serving the purpose of the launderer – making the strategy especially dangerous in the so-called year of elections.

Rodríguez says what is particularly concerning is Russia’s ability to embed its influence networks in different communities and launder information by “speaking the domestic language and understanding the domestic grievances.”

Recent CIR analysis shared with Bloomberg revealed how X (formerly Twitter) accounts being used to promote Russian interests in South Africa are attempting to rally support for a new party backed by former President Jacob Zuma. Investigators identified several accounts that praised Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and drew parallels between Zuma’s leadership and Putin’s. One such account has around 170,000 followers and regularly interacts with other users to amplify its reach – at times generating over 1 million impressions per post.

Ahead of elections in the U.S. and Europe, military aid to Ukraine has been a key topic for debate, and American officials have expressed concern that Russia will increase support for candidates opposing Ukrainian aid.

Recent reporting by the New York Times details Russia’s intensified efforts to amplify arguments for isolationism, with the ultimate aim of derailing military funding for Ukraine. While the initial arguments against additional aid may be organic, it is the amplification that is being “engineered” by Russia through the replication and distortion of legitimate news sites – a clear example of the information laundering described by Rodríguez.

Another key Russian tactic to destabilise support for Ukraine is through attacks designed to discredit and undermine the country’s political figures. The Washington Post recently uncovered a Kremlin disinformation campaign designed to push the theme that Zelensky “is hysterical and weak”, and to “strengthen the conflict” between Zelensky and Zaluzhny – the top military commander he dismissed in early February.

One senior European security official commenting on the campaign told The Washington Post: “Russia survived and they are preparing a new campaign which consists of three main directions: first, pressure on the front line; second, attacks on Ukrainian infrastructure; and thirdly, this destabilization campaign.”

Fragmented societies and social media bubbles

But as democracies around the world prepare to open their polling booths, U.S. officials have also warned that Russia may be attempting to move beyond targeting individuals, instead sowing seeds of doubt over the future of democracy itself.

A U.S. review of elections between 2020 and 2022 identified 11 contests in nine countries where Russia attempted to undermine confidence in election outcomes. More subtle campaigns – which attempted to cast doubt and amplify domestic questions about the reliability of elections – were identified in a further 17 democracies.

While content moderation by Silicon Valley companies has been strengthened in the wake of the 2016 U.S. elections, research has repeatedly raised the issue of comparatively inconsistent and weak moderation of non-English language content, leaving hundreds of millions of voters particularly vulnerable to campaigns and strategies that Russia has expertly refined.

Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen previously warned that 87% of Facebook’s spending on combating misinformation was spent on English content, despite only 9% of users being English speakers – a disturbing finding for non-English speaking voters as they head to the polls. Meanwhile, after Elon Musk’s controversial takeover of X, disinformation and hate speech reportedly surged.

Research indicates that public trust in government, the media and democracy is waning, while conspiracy theories have flourished in recent years, particularly in the wake of the pandemic, a trend noted by Rodríguez:

“Societies are suffering a post-covid effect, we’re still extremely divided, and audiences are being held in social media bubbles. It’s very easy to disseminate false narratives and amplify them online, shaping cognitive processes and impacting public perceptions.”

Coupled with weak or understaffed content moderation from social media companies, this fragmentation provides fertile ground for influence operations to thrive, Rodríguez warns.

“The recent changes in social media platforms like Twitter favour this trend. It is a very volatile environment in an electoral year.”